Where Cameras Cannot Go

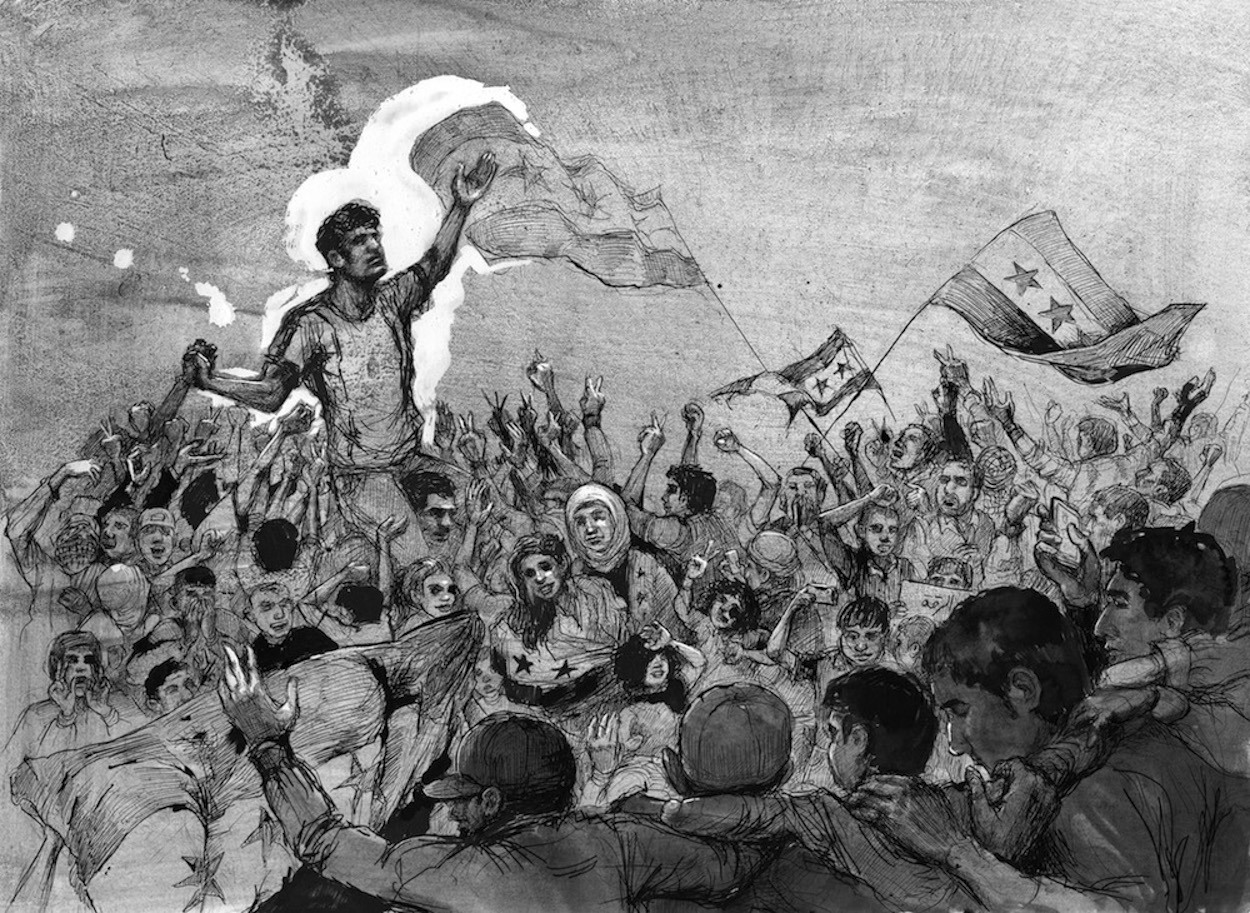

Marwan Hirsham risked his life to tell the story of life under ISIS. Molly Crabapple has used art and words to report from Occupy to Guantanamo. Together, they have created a uniquely powerful memoir of coming of age during the Syrian civil war.

Syrian journalist Marwan Hisham and artist-writer Molly Crabapple have joined forces to create Brothers of the Gun, the powerful memoir of Hisham’s coming of age during the Syrian civil war. Marwan risked his life as a young journalist reporting on what life in Raqqa was like under Islamic State control, before ultimately fleeing the violence to live in exile in Turkey. Molly came to attention drawing the frontlines of Occupy Wall Street, before covering, with both words and art, Lebanese snipers, labour camps in Abu Dhabi, Guantanamo Bay, and more.

We spoke to Molly and Marwan about co-creating this vivid portrayal of his experiences, and creating what they call a “story of pragmatism and idealism, impossible violence and repression, and, even in the midst of war, profound acts of courage, creativity, and hope.”

How did you come to work with Marwan?

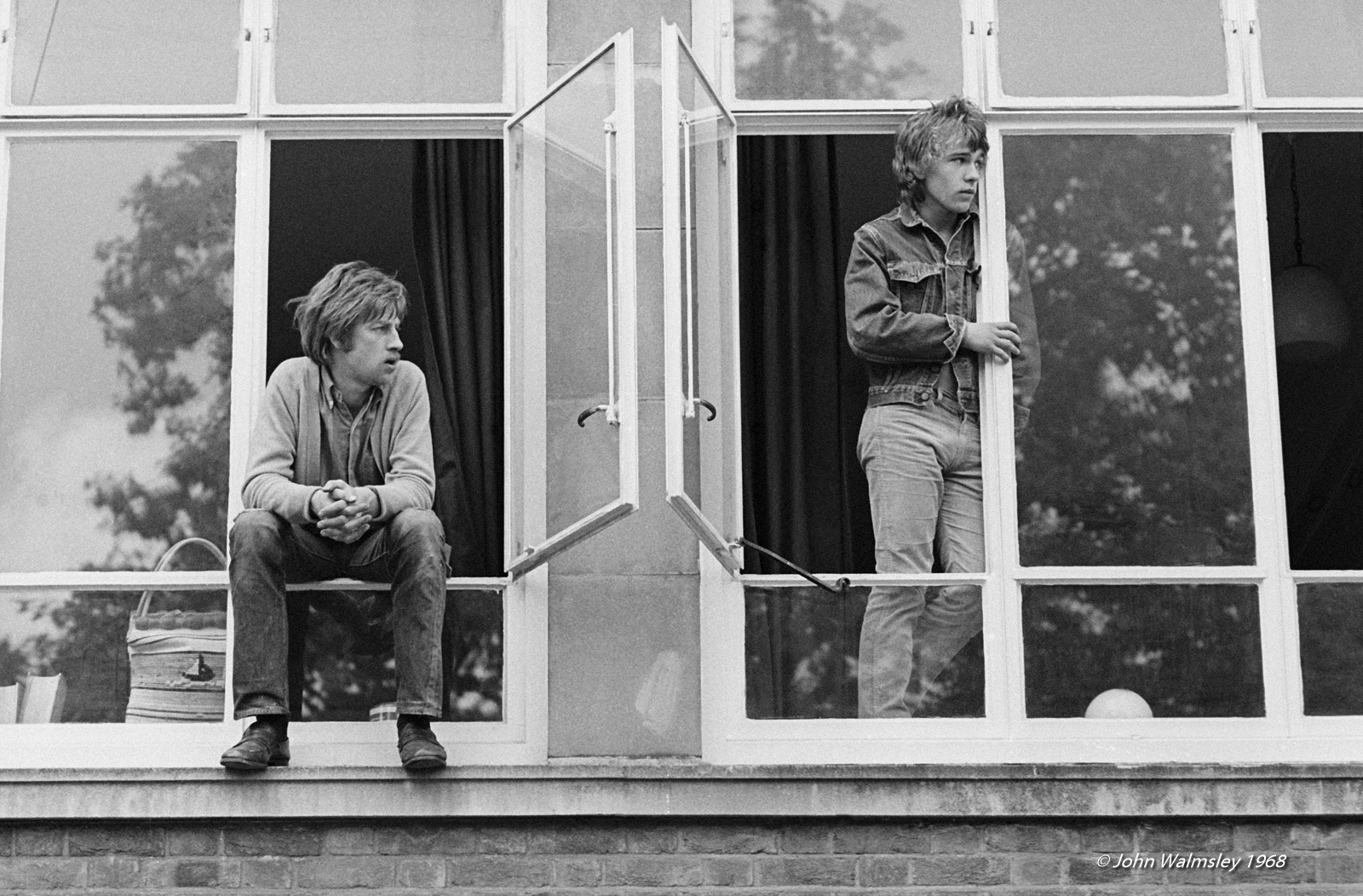

Molly: I've been reporting on the Syrian war and Syrian refugees since 2013, when I first went to the unofficial camps in Lebanon's Bekaa valley. Originally, I knew Marwan through Twitter, and he was a source for my own articles on ISIS, but as I began studying Arabic, he taught me so much, and we became friends. In the summer of 2014, I asked him if he happened to have any cellphone pictures of Raqqa, his hometown, which was then under ISIS occupation, for me to draw from. Three collaborations for Vanity Fair later, we decided to do a book.

Marwan, how does it feel to see your experiences expressed in the visual art in this book?

Marwan: I think Molly’s art added another dimension to the photos I took and revived old memories. She couldn’t have presented them in a more artistic and vivid way. Art perpetuates images in my opinion, and the way these drawings complemented the text was highly interesting to me.

What led up to the decision to do the book in this style?

Marwan: The three pieces we’d done for Vanity Fair from Raqqa, Mosul and Aleppo more than three years ago, which we built the book idea on. We were encouraged by the positive reception. We knew that we could make a book together that neither of us could have done alone, and this was the basis of our collaboration in the first place.

What was the process of translating Marwan’s experiences into visuals?

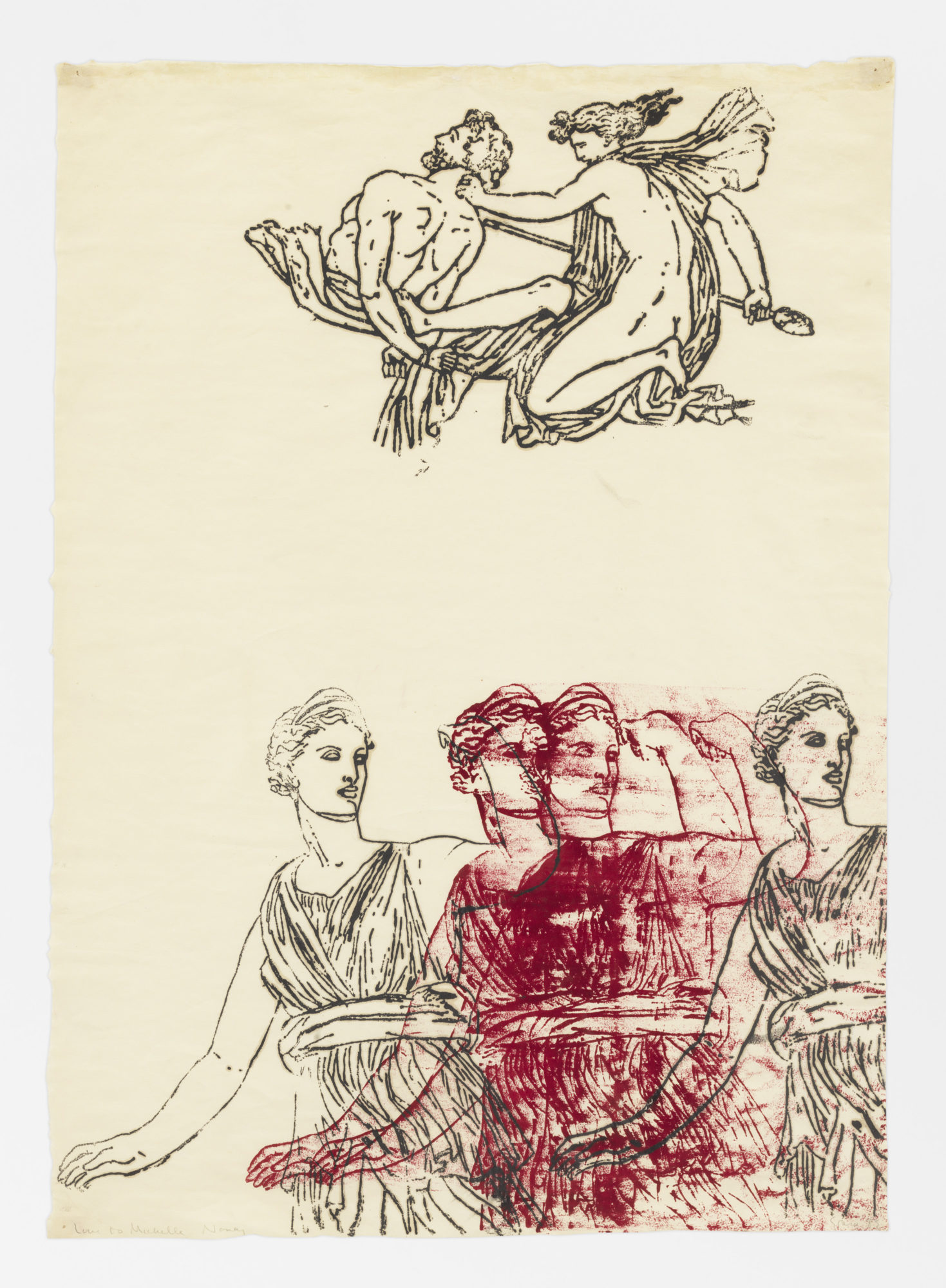

“You have to read words, but art jumps through your pupils, into your brain and heart, often without you letting it.”

Molly: While at first I worked from photos Marwan took, at massive personal risk, for Brothers of the Gun, we had to draw places where a camera could not go, like checkpoints, or a room with enslaved Yezidi women, or a religious school where Marwan spent some unhappy years of his childhood. For these, I relied on Marwan's memory. We worked so closely, my interviewing him, then sketching, then him correcting my sketches, that though the drawings were done with my hand, I consider them – just like the text – equal co-creations. Not a line in this book, either in words or in ink, belongs to either of us alone.

Why did you feel it was important to tell Marwan’s story through this composite blend?

“I realised I had a rare access to life under ISIS that many journalists paid their lives for, and since risk was involved in merely living, I was driven by my desire to do something meaningful”

Molly: Art is visceral in a way that words are not. You have to read words, but art jumps through your pupils, into your brain and heart, often without you letting it. Also, people in the US have such a thin, impoverished understanding of what life in Syria is, and we wanted to show them Marwan's world as well as tell them.

Marwan, what was it like for you to risk your life to write about what was happening in Raqqa?

Life in Raqqa after January 2014 was a daily risk. ISIS built a system that watched everyone, and people were humiliated or executed for any reason. I realised I had a rare access to life under ISIS that many journalists paid with their lives for, and since risk was involved in merely living, I was driven by my desire to do something meaningful. Obviously, my being a local, and thus treated as a subject of ISIS’s caliphate, paved the way for undercover work.

How do you feel that illustration serves your project of journalistic storytelling for the stories you have worked with?

Molly: I've been lucky enough to report with words and art all over the world, from Guantanamo to Gaza, to hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico. In a time when photography is utterly ubiquitous, I believe that art has an extra power – the mark of human care, and of the human hand.

How do you feel that illustration serves your project of journalistic storytelling for the stories you have worked with?

Molly: I've been lucky enough to report with words and art all over the world, from Guantanamo to Gaza, to hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico. In a time when photography is utterly ubiquitous, I believe that art has an extra power – the mark of human care, and of the human hand.

What have you learned from using art as a tool for activism?

Molly: I don't know if I've learned anything, to be honest. Whether my work is in my sketchbook, on a protest poster, on a nightclub poster or illustrating Brothers of the Gun, I have the same obsessions with craft, line, visceral beauty, and truth against cliché.

What effects to do you hope this book might have for situation in Syria?

Marwan: I don’t think a book can change much in Syria at the moment. But there’s nothing more rewarding than seeing readers, not just from Syria, but from different backgrounds and different countries, identify with it. Also, Syrians need to address the primarily social problems that Molly and I tried to list in the book, and bit by bit, hopefully, Syrians can challenge the wrong convictions they inherited from their ancestors and break taboos.

Words by Callie Hitchcock

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.