Envisioning the Anthropocene

Over the last five years, three visual artists have documented the staggering reality of our current geological epoch – ‘The Anthropocene’ – collaborating with a team of scientists to visualize our indelible signature on the planet.

The Anthropocene Project at Fondazione Mast in Bologna, Italy is the culmination of five years of intensive research from a collaborative scientific, curatorial and documentary team. The project seeks to document the indelible human footprint on the earth through the photographs of Edward Burtynsky, films by Jennifer Baichwal and augmented-reality installations by Nicholas de Pencier.

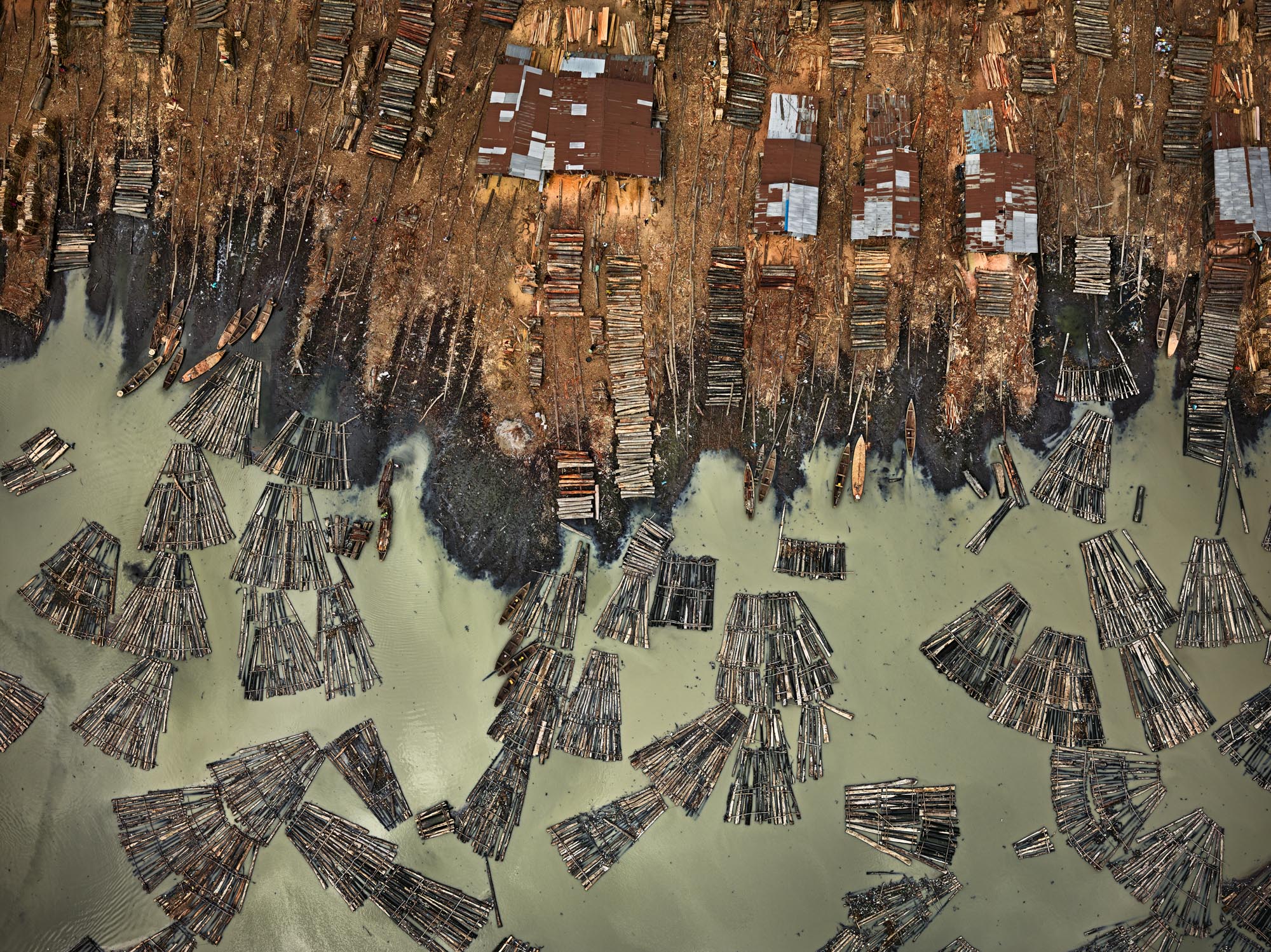

The project draws on research by the Anthropocene Working Group, who have proposed to officially name our current geological epoch ‘The Anthropocene’, meaning the period in which human activity has been the dominant influence on the environment. Phenomena such as the deforestation of old-growth forests, open-pit mining, the ubiquity of plastics and concrete, and the loss of elephants and rhinoceroses in Africa provide support for the Anthropocene Working Group’s hypothesis, as well as the visual focus of the exhibition.

Good Trouble spoke with photographer Edward Burtynsky about the aims of the project and its implications for the future.

How do you define the Anthropocene?

As part of the Anthropocene book, we wrote a glossary of terms that we had approved by the Anthropocene Working Group. ‘Anthropocene’ is defined as the proposed current geological epoch, at present informal, in which humans are the primary cause of permanent planetary change.

Carrara Marble Quarries, Cava di Canalgrande #2, Carrara, Italy 2016 © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London / Howard Greenberg and Bryce Wolkowitz Galleries, New York

When did you first hear about the term ‘Anthropocene’ and what was your initial reaction?

“Our mission would be to evangelize the word ‘Anthropocene’, raise awareness for the issues it presented, and bring both the word and its implications forward in people’s consciousness.”

We have been aware of the word and concept for well over a decade, and it was when we were wrapping up Watermark that Jennifer suggested that this is what we should title our next project. I wondered if a project titled with an unfamiliar term could be successful. It was then that we decided our mission would be to evangelize the word Anthropocene, raise awareness for the issues it presented, and bring both the word and its implications forward in people’s consciousness.

How did you start working on this project?

By the time we started thinking about The Anthropocene Project, we’d already completed two feature documentary films — Manufactured Landscapes (2006), for which I was the subject; and Watermark (2013), which I co-directed with Jennifer…Conceptually, it seemed like the culmination of the work we’d already done together, and also all of the work in my career so far. We recognized the challenge of the term itself, but the importance of bringing awareness to this subject matter — to our collective, global responsibility for this planet — inspired us to pursue it.

Coal Mine #1, North Rhine, Westphalia, Germany 2015 © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London / Howard Greenberg and Bryce Wolkowitz Galleries, New York

What was the process like working across different disciplines as artists as well as alongside the scientists to create this exhibition?

Edward Burtynsky in Chile, 2017

The landscapes and places we photographed and filmed over the last five years have all been inspired by scientific evidence, each one an example of things like terraforming (deforestation of our old-growth forests, agriculture and open-pit mining), technofossils (the ubiquity of human-created objects like plastics and concrete), and extinction (the loss of elephants and rhinos in Africa at the hands of aggressive poaching for their ivory and tusks).

The research gets us started. We source out these places that represent the biggest, most shocking examples of these events. We learn everything we can about them, not just the operations, but the communities in these places as well. Then we try as hard as we can to physically get there, and of course once we do, we learn so much more. There are stories and moments from the people in these places all around the world that you will not find in a scientific journal or online article.

“There are stories and moments from the people in these places all around the world that you will not find in a scientific journal or online article”

Similarly, the integration of these new technologies in this project seemed like a natural progression. Baichwal and de Pencier's films have always brought a new layer and depth of understanding to my still photography. There are some things that the two-dimensional image cannot communicate. But film, and then this move into what I call Photography 3.0 — evolving into the third-dimension with virtual and augmented realities (AR and VR) — extends the possibilities of the art, both for the audiences and us as artists. And for a subject like Anthropocene, being able to have an immersive experience really brings that story home.

Dandora Landfill #3, Plastics Recycling, Nairobi, Kenya 2016 © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London / Howard Greenberg and Bryce Wolkowitz Galleries, New York

How have your ideas about the Anthropocene changed through working on this project?

“The greatest existential threat is thinking that the next generation will fix the problem”

When we began working on The Anthropocene Project, it still felt that there was ample time for a course correction. But over the course of the last five years, reading reports and stories, coming to terms with undeniable statistics in relation to our impact humans are having, we're definitely walking away with a greater sense of urgency. It's apparent that the time to act is now, and we cannot leave it to the next generation to deal with. The greatest existential threat is thinking that the next generation will fix the problem.

Uralkali Potash Mine #4, Berezniki, Russia 2017 © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London / Howard Greenberg and Bryce Wolkowitz Galleries, New York

So much of the human experience is grounded in interactions with the natural world. What do you believe are the philosophical implications for humans, given this major shift in the natural world order?

The philosophical question that comes to mind is whether or not we see ourselves as part of nature, or do we see it in fact as something outside of ourselves, something that is for our consumption? If it's the latter we end up with sort of a tragedy of the commons. If we continue with "business as usual" we risk experiencing the incredible loss of land biodiversity, and ocean life, and then of course all of the consequences that would follow.

“The philosophical question that comes to mind is whether or not we see ourselves as part of nature, or do we see it in fact as something outside of ourselves, something that is for our consumption?”

What do you hope viewers take away from this exhibit?

The initial goal was to bring the word Anthropocene into the public consciousness. I think in many ways, with the success of the two exhibitions and the release of the film in Canada, we have accomplished this.

The Anthropocene has also been a hot topic for the media the last few years, so when we go and speak to groups of people now and ask how many of them have heard of the word, more and more people are raising their hands. We’re no longer just speaking to a room entirely full of blank stares. Then, of course, the artworks and the film all bring attention, visually, to the various issues that address the Anthropocene. People are beginning to connect the dots, and understanding the extent of our collective human impact. Once you understand how you're impacting the world around you, you can begin to make more positive adjustments.

Words by Esther Hershkovits

Top picture Saw Mills #1, Lagos, Nigeria 2016

ACTIONS

The Anthropocene Exhibition is showing at Fondazione MAST in Bologna, Italy through September 22nd, 2019

Their documentary film, ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch, is out September 25th, 2019

Join a climate action group such as 350.org, Climate Reality or Extinction Rebellion

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.