The Problem With Tastefulness

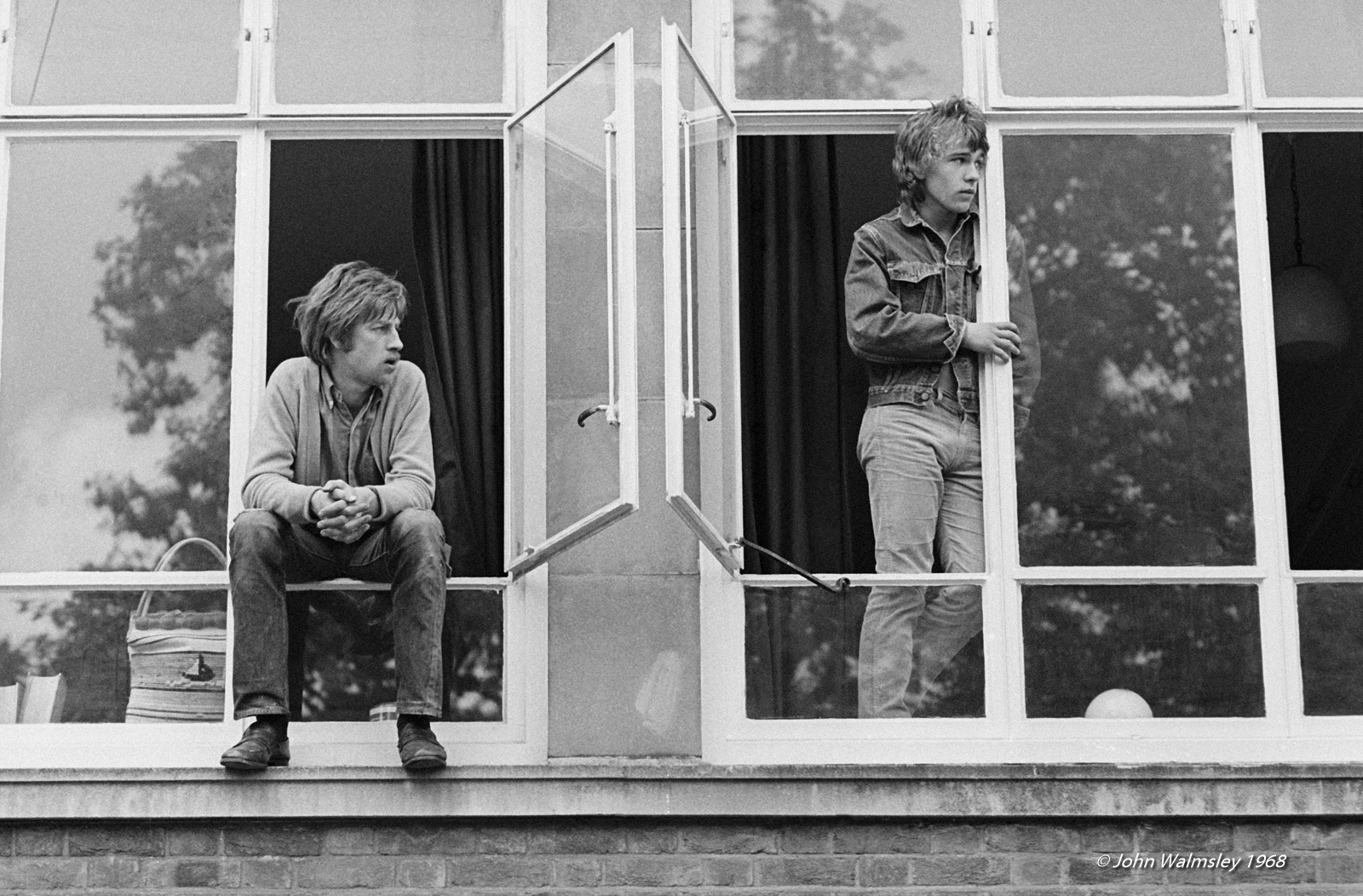

“Rules of taste appear as a means of control.” Read an extract from the incisive, angry and brilliant book ‘Steal as Much as You Can’, by Nathalie Olah

Kathy Acker once wrote that Andy Warhol had made it OK to be queer. She was referring of course to the fact that Warhol’s work shocked, thereby challenging existing rules of taste and allowing the trans, gay and bi people he called his friends not just to feel accepted but to have a greater degree of agency in shaping mainstream culture and the collective values of a generation. I don’t particularly like Warhol or his legacy of exploiting people to further his own celebrity, but I include his example to highlight the fact that he made cultural inroads by virtue of being controversial. He didn’t transform Western culture by writing something in the vein of so many of today’s pop-feminist or similar political ‘manifestos’, explaining in jocular, broadsheet-friendly terms the finer details of his friends’ amphetamine addictions and sex lives for the purposes of appeasing the middle classes. But, with the exception of a rare few outliers, such as writer Reni Eddo-Lodge, whose polemic Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race made one of the rare, direct and unapologetic affronts to the mainstream establishment in recent years, as well as Jordan Peele, whose films, including Get Out, have achieved similar gains within the movie industry, this is precisely what even our most experimental culture looks like today, feeding middle-class caricatures of a youth culture, as well as a plethora of social issues, that few on the ground actually recognise. The mainstream media can wield any number of works detailing the experiences of trans people, for example, as proof of its progressive and inclusive agenda, but where has the anger gone? The rage and the despair? Where are the Derek Jarmans? The Leigh Bowerys? The Grace Joneses? Where are the artists like Keith Flint and Tricky, who crept onto our TV screens and terrorised our mums? Against everything, these artists made inroads into pop culture, shaping and expanding the horizons of the British public. Where is even our equivalent of George Michael – a popstar whose provocations to the homophobic entertainment industry and media, and the political statements that he made during TV interviews, seem strangely unthinkable to us in the current climate? In the pervasive and ever more limited rules of tastefulness that now reign supreme, even these once celebrated attendants of pop culture would not be permitted – and it is this that is increasingly contributing to the internet, for good or bad, becoming the real terrain of today’s culture wars, rather than the tired establishment routes whose tyrannical constraints prevent anything meaningful and authentic from ever being expressed.

“Where has the anger gone? The rage and the despair? Where are the Derek Jarmans? The Leigh Bowerys? The Grace Joneses? Where are the artists like Keith Flint and Tricky, who crept onto our TV screens and terrorised our mums?”

Broadly speaking, though not in all cases, these challengers to the mainstream also hailed from low-income backgrounds. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the elitist risk-aversion that set in post-2008 has therefore not only created a cultural climate that is unrepresentative, but by eliminating working-class vernacular art and storytelling – made vivid by its struggle and its urgency – also created a cultural climate of the most prosaic and unremarkable kind. Identity politics have played an important role in recent years in helping millions of people live a more complete, honest and truthful life, and allowed many more people than ever before to feel more accepted by society. But any effort to promote greater inclusivity that neglects to consider how race, gender, sexuality and disability intersect with class, is incomplete. For most people, the prejudices faced on account of any factor of identity will be intimately connected with the poor conditions they face at work, their interactions with customers when working in the hospitality industry, for example, and their reliance on bureaucratic systems that the middle classes are able to buy their way out of. Therefore, any effort to mainstream a more inclusive attitude towards any one of these factors of identity must also require us to consider them through this socioeconomic lens.

The type of sponsored event championing various issues of identity politics that we’ve seen explode in recent years – usually hosted in the exhibition halls of Somerset House and attended by a core strain of magazine and PR person living in London – sadly won’t achieve this, and only constitutes a complex version of the dreaded advertorial, or similar. What’s more, it has seemed at times over the past decade that the liberal media has relied on these fairly facile gestures to preserve its progressive credentials, while crucially failing to address the mounting class struggle that has been taking place all around it; often amplifying the voices of influencers championing single-issue identity causes, while neglecting to document the anger of working-class people of all races, genders and sexual persuasions up and down the country, and neglecting to acknowledge its own part in a deeply classist society.

As the media pulls further and further away from the lived experience of working people, and class becomes increasingly denied, its rules of taste also start to appear more vividly as a means of control. This is my main reason for challenging the increasingly tepid and predictable output of our cultural institutions, and for sometimes championing work that offends the sensibilities of its middle-class gatekeepers – not because I necessarily have a vested interest in the work itself, but because any challenge to an all-pervasive and seemingly inescapable neoliberal system depends on the right for challengers to exist. What (Angela) Nagle has characterised as ‘transgressive’ art and culture in Kill All Normies – thereby implying that it is also gratuitous – actually serves an invaluable role in creating a more critical and responsive society. That’s because mainstream cultural output that shocks, scares, challenges and surprises us also forces us to participate, and forces us to look inward and reflect on the emotional responses it creates. It works in the opposite way of the very easily digestible culture promulgated by today’s gatekeepers, and creates a climate in which we all become more alert and critical in our political judgements. I could read as much theory and commentary on race relations in western culture as I wanted and still not experience the palpable embarrassment I did from watching five minutes of Get Out. Such work is necessary for making all of us more cognisant to any strain of cultural bigotry and oppression, but it is particularly important for remaining aware of the many quiet and subtle ways in which neoliberal politics shapes our daily lives and perpetuates a polite oppression. In this sense, we need horror and transgression not only to allow for the expression of rage and anger that many of us rightly feel, and not just to allow for satirical output capable of skewering the incumbent elite, but to keep all of us more alert to the hypocrisy of respectable politics and culture, whose mild-mannered delivery has for too long sought to distract us from the violence of structural inequality that is contains and conceals.

Tastefulness is also highly rigged and hypocritical. After all, an aristocrat’s son wearing a tracksuit remains an aristocrat’s son, while a wealthy footballer driving a Lamborghini that he has chosen to paint in camo will forever be excluded and derided by the establishment. In this unilateral arrangement, the middle and upper classes are free to mine working-class culture for whatever purposes they like – freely switching between the signifiers of their class to whatever sportswear is approved by Hypebeast – while their working-class peers are ordered to conform to a narrow set of good taste principles defined by the establishment in order to be accepted and approved. This is something like an inversion of the ‘code-switching’ phenomenon referred to by US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in an April 2019 Twitter thread, following a claim made by President Trump that her ability to switch vernacular depending on audience group constituted a lack of political integrity and authenticity. Ocasio-Cortez hit back, arguing that the necessity for ethnic minority and working-class people to develop secondary speech patterns in order to succeed at work amounted to one of the most pervasive and unchallenged forms of xenophobia and class bias in America. It also lent a poignancy to her previous endorsement of US rapper Cardi B, famous among other things for the unapologetic use of her Trinidadian/Dominican-by-way-of-the-Bronx accent, and whose meteoric rise to fame constitutes one of the most vivid and hopeful symbols of working-class participation in mainstream culture of recent years. When used in reverse – that is, when the rich cosplay as the working class – it functions in much the same way as the ‘cool-hunting’ phenomenon outlined previously, erasing and thereby negating the working-class experience.

“An aristocrat’s son wearing a tracksuit remains an aristocrat’s son, while a wealthy footballer driving a Lamborghini that he has chosen to paint in camo will forever be excluded and derided by the establishment.”

Think of its core tenets too, and it becomes obvious how far tastefulness is used as a way of modulating and silencing cultures that diverge from the status quo. Good taste is often defined as being understated, inoffensive, muted and calm. On the flip side of this, young inheritors of the white middle class seeking to lay claim to something cool and edgy are increasingly drawn to aspects of working-class culture that they judge to be gauche, exciting and strange. This takes us back to the resurgence in terrace culture mentioned previously and its concentration in recent years among affluent, privately-educated people, particularly those working in fashion, who show little regard for how this fetishisation only makes class divisions more entrenched, by further pushing the working-class experience into the realm of morbid spectacle.

Similarly, we see on the pages of magazines aspects of the working-class experience used to sell fashion – Balenciaga jackets shot against council-estate backdrops in an assertion by its mostly white, mostly middle-class authors, including photographers, stylists and editorial staff, of the inferiority of this social milieu; an ironic juxtaposition that could not exist were all those involved not signatories to the belief that the cultural background against which it is set constitutes something disgusting.

I first encountered this flagrant and semi-ironic use of class interplay when, in an effort to vindicate my working-class parents who’d been denied the opportunity for further education themselves, and in the somewhat vain hope of improving conditions for all of us, I found myself in the halls of Oxford as an 18-year-old student.

With the exception of a few good friends, most of whom came from working-class state-school backgrounds and found themselves feeling equally isolated and confused, the experience was unsettling and fairly disruptive to my overall wellbeing. In addition to there being widespread and unchecked misogyny, classism and bigotry of almost every possible variety, Oxford was also one the most culturally barren places I have ever encountered. For the privately educated, university seemed less an exercise in wanting to genuinely understand the world around them and more an endless game of debate and one-upmanship, where the final goal wasn’t to establish truths or to find solutions to any given problem, but to simply win. In this game, reading materials were no longer entry points or ways of thinking about a given subject, but provided a stock of quotations used as collateral in arguments whose basis never extended beyond the person’s own biases and judgments. Rewards were given to those who spoke most persuasively, who had the greatest command and confidence in their delivery, and who, I realised, were able to most successfully mimic the styles that were peddled in the House of Commons and, increasingly, the mainstream media.

In many ways, what I encountered at Oxford seemed to flout every convention of the academic or scientific approach as I had understood it. What I witnessed instead were young people learning ways to justify their biases and confound anyone who challenged them through equivocation and an arsenal of quotations. This created the grounds on which most privately-educated people who I met there seemed to believe that the purpose of university was simply to hone and refine their all-powerful minds, rather than putting those minds to work in the service of some greater cause or purpose. It was a place where everything had been stripped of greater meaning, beyond serving as collateral in the arguments that were being formulated by these precocious young graduates of abject privilege. If culture is the expression of a collective identity and of a shared sense of belonging, then it was little surprise that, in this hub of individualism, where the power of ego reigned supreme, culture was almost nowhere to be found.

Blur bassist Alex James’s cheese festival might serve as an extreme example of the twee approximation of what most middle-class people in Britain now understand to mean culture, but aren’t most festivals really just a variation on Alex James’s cheese festival, insofar as they are largely the preserve of a white establishment so devoid of any essential connection to a wider community or collective identity, that the only means it seems to have found for self-expression is dowsing its face in glitter? This, I might add, was the preferred pastime of most people I encountered during my three fairly difficult years at Oxford.

And yet, those accusing the over-tanned, Aaliyah-impersonating or bindi-toting Home Counties transplants to Glastonbury or Notting Hill Carnival every year of using their culture as a costume, might be good enough to remember that these are the hapless orphans of a culture that has long since departed – smiling polaroid avatars, swirling forever on a sea of pastiche.

Steal as Much as You Can by Nathalie Olah is published by Repeater Books, 2019

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.