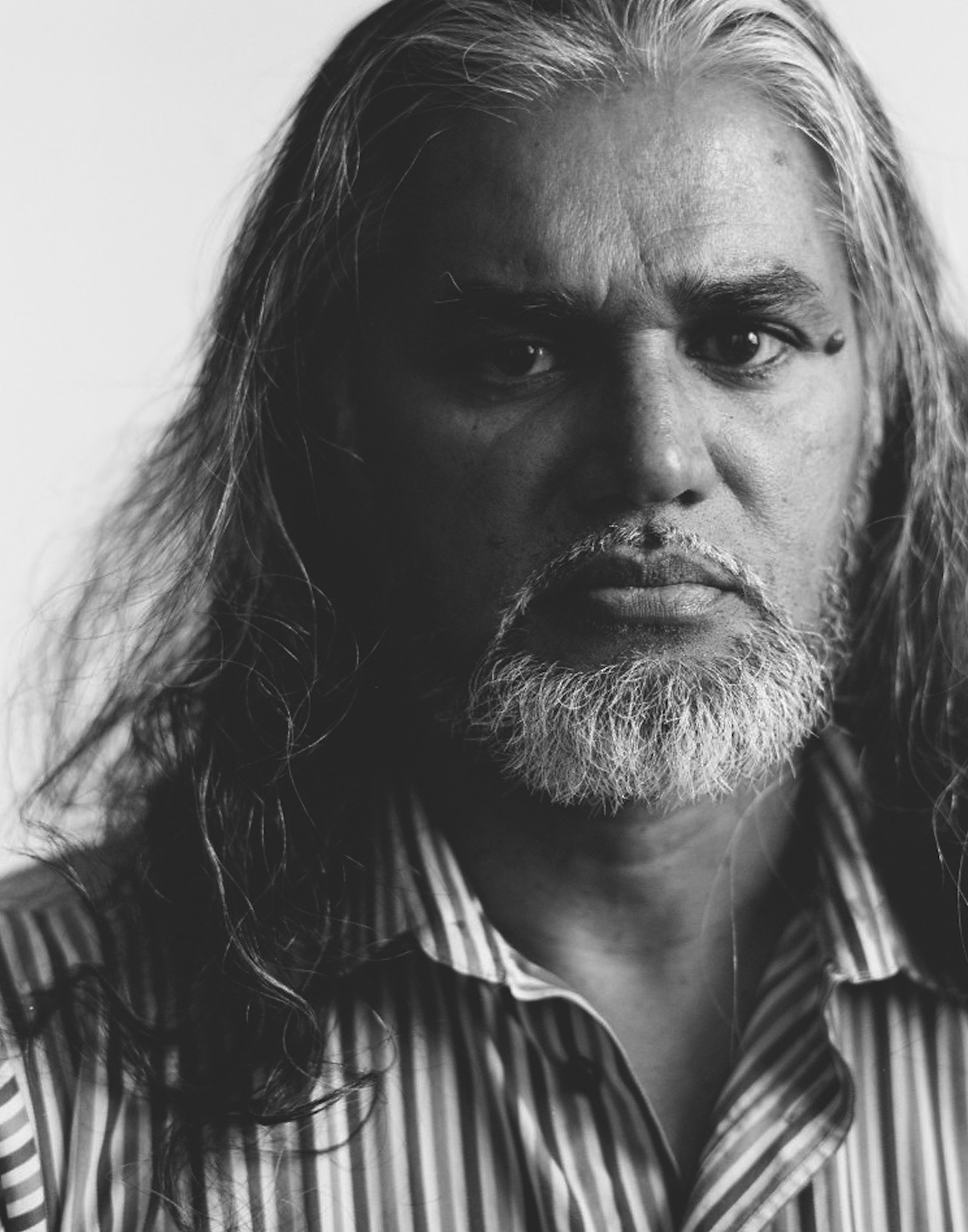

Poetic Justice: Ekene Ijeoma

From HIV infection rates to mass incarceration, New York-based artist Ekene Ijeoma draws on data to create powerful installations that confront injustice while searching for solutions.

Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis was a fascinating and enlightening recent show at the Museum of the City of New York that examined the history of the city’s battle with infectious disease – a fight that, in its words, involves “government, urban planners, medical professionals, businesses and activists”.

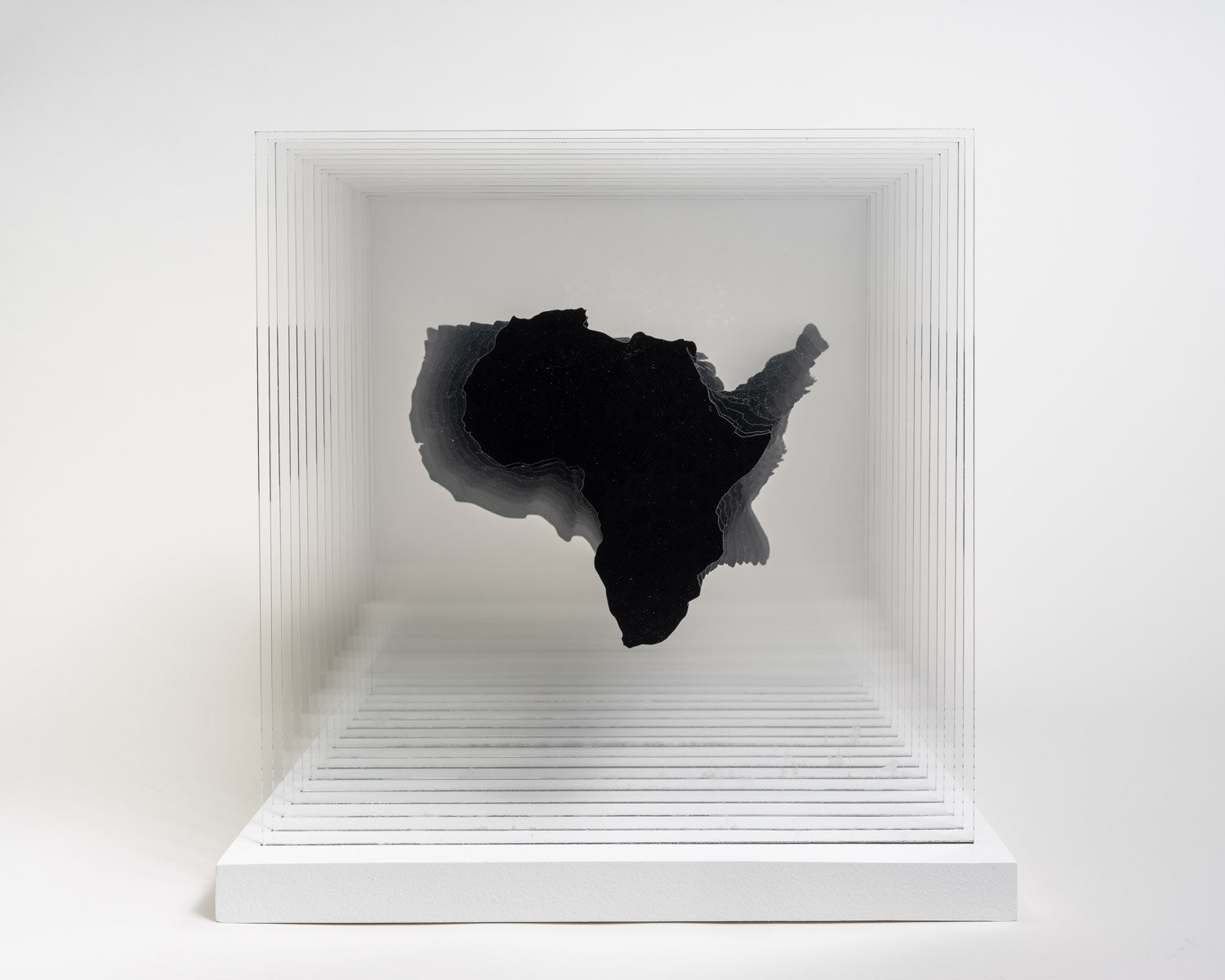

The relationship between people and pathogens has always had a cultural and political element in terms of what happens and to which communities. On display at the exhibition was a new sculpture called Pan-African AIDS, which explored the “hyper-visibility of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa and the hidden one in black America”. Between 2008 and 2015, while the rates of HIV/AIDS infections in Africa went down, the rates in the black population in the USA actually went up. A series of plexiglass panels transitioned between representations of the two populations at a rate exactly equivalent to the rise of infection in the US, sliced up into eight sections for each year.

“It’s shocking, because we’re in America. We’re supposed to be this first-world country. Yet you have populations here that are experiencing the same conditions as in so-called developing countries.”

Commissioned by the museum in partnership with London’s Wellcome Trust, the sculpture was the work of 35-year-old Ekene Ijeoma, a New York-based multidisciplinary artist and designer who uses technology and data to create powerfully affecting sculptures, installations, websites and performances. “The work I'm doing and the context of it is meant to be seen and discussed,” says Ijeoma, picking at a croissant on the plate in front of him. Softly spoken and sometimes self-deprecating, he often offers a ‘maybe’ or a ‘kind of’ at the end of his lengthier discursions. When an idea takes him, though, he is forthright: “It’s not for sale. For me, it’s about getting the ideas and the issues out there through the work.”

For Pan-African AIDS, Ijeoma worked with an epidemiologist, researching academic reports about rates of infection in African countries where the fight against AIDS was funded, and in black populations in America where it wasn’t. “I just started making all these connections between race, health and inequality,” he says. “Men who have sex with men in Harlem, their rates are about the same as some of the countries with the highest HIV prevalence rates like South Africa.

“It’s shocking, because we're in America... We're supposed to be this first-world country. We’re supposed to be the developed country. Yet you have populations here that are experiencing the same conditions as in so-called developing countries.”

Ekene Ijeoma, Pan-African AIDS, 2018, Vinyl on Plexiglass, wood. Credit: Isometric Studio

Ijeoma grew up in Fort Worth, Texas. Both of his parents are business owners – his mother owns a salon, while his father runs a bookkeeping shop. He didn’t particularly enjoy Texas, specifically Fort Worth: “I mean, it wasn't a place for me. I don't have many thoughts about Texas. I left as soon as I could.”

He went to college at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York state. “I thought it was closer to New York City than it is,” he laughs. (Narrator: It’s actually 350 miles away, near the Canadian border.) In high school he focused on art, but his parents didn't want him to go to art school. So he started taking design courses while continuing to make art. While studying “how to make banking apps”, he learned software programs like Processing, which enabled him to begin drawing with code. “I started using technology and it changed the way I thought about art. I was just making work. I still don't know about the art world.”

Ijeoma is ambivalent about whether he is an artist or a designer. “I'm an artist who uses design to make work,” he shrugs. “Like, design is the tool. Art feels like the product.”

Courtesy of Ekene Ijeoma

His first major project that came to people’s attention was The Refugee Project, an interactive map created in collaboration with Hyperakt design studio. “It showed, for the first time, every country affected by the refugee crisis,” he says. “We visualised the data but what it really was, for me, was changing the way we see an issue represented in the media.”

“Refugee migration was an issue mostly seen through photography – the photo of the Afghan girl in 1984. More recently, when the European refugee crisis started, you had the Syrian boy on the beach. But between those two photos, the media wasn't really talking about refugee migration as an issue.”

When they did, it was always in relation to single countries, such as Syria. “But middle-eastern Africa had been experiencing some of the largest numbers of refugee migration consistently for decades. So it was to show more perspectives, to look outside the frames of photography that just focus on individuals and look at the larger system of the refugee crisis itself. It's more than one girl in Afghanistan.”

On the one hand, we are told people supposedly need simple stories and faces, otherwise they’re not able to impart information. On the other, we can see the dangers inherent in boiling everything down to personal narrative – the breathless palace intrigue surrounding Donald Trump and his court of corruption, or the endless political soap-opera surrounding Brexit, that drowns out almost all discussion of actual issues. Who’s in? Who’s out? It’s life and politics reduced to the banal stagings of a reality show.

“People need characters,” agrees Ijeoma. “You know, one of the criticisms of that work was that it was lacking in just that. And that's fine! It was a pragmatic way of showing the issue – it needed to be done. The data for the refugee crisis had been collected for decades, it just wasn't being visualised in the way we did.”

He talks about Colors magazine in the 90s, and its innovative visual reframing of the refugee crisis and AIDS. “Those things are still being represented in the same way, but nothing's changed,” he says. “Does that mean this representation, was that working? Or was it not working? Why hasn't it changed? If the issue hasn't changed, why hasn't representation changed to affect that? For me, using the means of today to make work about today is what I’m doing, and seeing technology as the way to do that.

“We have to talk about why a lot of people thought we were living in a post-racial society. Why do they think it’s post-racial? Oh, it’s because they’re not experiencing the same discrimination. How can we communicate, create visibility around this?”

Tibor Kalman, Colors Magazine Issue 4, 1993

“I'm embracing the space between facts and feelings. When I feel something, I want to be able to say it's based on something. I don't want to say: ‘Oh, I just woke up and I'm feeling this way. Which point do I want to use for this?’ You know, like I wake up and I'm feeling this way about race in America.

“Then we have to talk about why a lot of people thought we were living in a post-racial society. Why do they think it's post-racial? Oh, it’s because they're not experiencing the same discrimination. How can we communicate, create visibility around this, so there's accountability around the ‘Why am I feeling this way?’ That's what it is.”

Wage Islands (2015) is a 3D map of New York City based on housing costs, submerged in a tank of dark blue water. As a viewer presses a button to increase the hourly wage, areas of the map slowly lift above water to show the parts of the city low-wage workers can afford to live in at that wage level. When the button is released, the wage reverts to legal minimum and the city sinks beneath the water.

“Wage Islands was (created) when I was reaching towards more poetic ways of using data,” says Ijeoma. “I was using a geographical map of of waging, housing and inequality in New York City, but the locations weren't as important as the fact that out of all the space in New York City, there just weren't a lot of spaces that minimum-wage workers could afford to live.”

Deconstructed Anthems (2017) is an ongoing project, a series of music performances in which a self-playing piano and music ensemble deconstruct 'The Star-Spangled Banner’, repeating it multiple times while removing notes at the rate of mass incarceration, ending in silence. A haunting performance at the Day for Night festival in Houston, Texas, included Emmy-winning pianist Kris Bowers, Blue Note trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and Grammy-nominated bassist Burniss Earl Travis.

The US imprisons more of its citizens than any other nation in the world. The jail population has exploded from less than 200,000 in 1972 to a scarcely comprehensible 2.2 million today, and it’s an issue that, like so many things in America, disproportionately affects people of colour. The statistics are shocking: one of every three black boys born in the USA today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime, as can one of every six Latino boys, compared with just one of every 17 white boys, according to the ACLU.

Ijeoma knew he wanted to use the national anthem to speak to the history of black people in America. At first, he was focused on historic centres of black wealth (known as ‘black Wall Streets’) at the turn of the 20th century. Greenwood, Tulsa, had one of the biggest concentrations of African-American businesses in the US until 1921, when white residents rioted, massacred hundreds of black residents and burned the entire neighbourhood to the ground.

Credit: Theo Civitello

“The idea was to look at overall disenfranchisement and divestment in the black populations since 1900,” he says. “I had been talking to the Vera Institute of Justice, who have one of the most comprehensive, I think, collections of data on mass incarceration in the nation.”

During the performance, as the notes slowly disappear from the anthem, it’s a powerful metaphor for a national identity decaying from the inside out, with parts of its collective identity literally disappearing over time – the people that should make the country what it is: “Juxtaposing something that is supposed to represent the American dream with something that's the opposite of it,” he adds. “In a lot of ways, that’s the black experience in the US. Especially in relation to mass incarceration… We’re supposed to keep believing that we're living the dream but we're not. Yet we still have to sing the same song.”

The piece was performed at the Kennedy Center in DC in a shortened version, and Ijeoma explains how he created custom software to compose the music and remove the notes. “I worked at the national level,” he says, referring to the data it draws from, “but I can also focus on a city or a state, and change the composition based on where it's being performed.”

He could see it in the future being adapted for a symphony orchestra, or perhaps a gospel choir. But jazz is all about finding freedom amid constraints, which is why he found it such a powerful way of exploring this idea: “The story of jazz is the story of black people navigating systems in the US.”

“People have been presented all the facts and no one is acting on facts. Everything’s based on facts, but we’re trying to translate that into an informed feeling. How can you meet people where they’re at?”

In 2019, Ijeoma became founder and director of Poetic Justice at MIT Media Lab, a group that sets out to merge different creative disciplines to create ‘art representations and interventions for problem-finding and solution-finding’. “It's just me taking everything I've been developing over the last five years and expanding that through their facilities and resources,” Ijeoma says. “Firstly, it’s one of the first art groups at MIT Media Lab. Secondly, it's about the third social justice group there, out of 25 labs. And I think there's been maybe one other black male that's ever done it.”

Ijeoma says he was overwhelmed by the amount of applications he received, but also their generosity: “People really share a lot. It's difficult because I'm I want to be able to support all this work, but I have to focus on this idea that I'm trying to create with Poetic Justice. We're not just making work about social justice. We're trying to speak to social justice with poetry… Not literature but, how can we say this in the most poetic way? How can you find a medium for the message? Because not everything can be a website. Not everything can be a sculpture.”

“We've had all the facts. People have been presented all the facts and no one is acting on facts… So, what we're doing with our work is – everything’s based on facts, but we're trying to translate that into an informed feeling. How can you meet people where they're at? The embodiment has to be different. That's what we're exploring.”

Writer, editor and consultant based in London /New York