Paris in Flame

France has a rich history of protest and revolt, but how does the ‘gilets jaunes’ movement fit into the picture? Two young Parisians, a photographer and a writer, give their perspective on this latest movement…

Photos by Mathieu Richer // Words by Léa Boehringer

“Résiste, prouve que tu existes,” sang France Gall.

Gall disseminated the infamous message of Albert Camus’ The Rebel: "To be, the man must revolt.” In France, now more than ever, to resist is to exist.

The movement of gilets jaunes [yellow vests] first broke out last October in response to a new domestic consumption tax on energy products, the TICPE. One of the main consequences of TICPE was the increase of the price of gasoline, which would have principally affected people who live in the countryside and need their cars to go to work.

The gilets jaunes first began by placing yellow vests on their dashboard and blocking traffic roundabouts in the provinces. Social media allowed for a rapid expansion of a once regional movement. On November 17, 2018, the gilets jaunes organized a demonstration at the largest roundabout in France: Place de l’Étoile, known worldwide as L’Arc de Triomphe.

It is best described by the French idiom: “la goutte de trop” [one drop too many] i.e. the straw that broke the camel’s back. That moment when we can no longer remain passive, when we must revolt. The gilets jaunes arose from a loss of patience with the French system that so flagrantly lacks consideration for the working class.

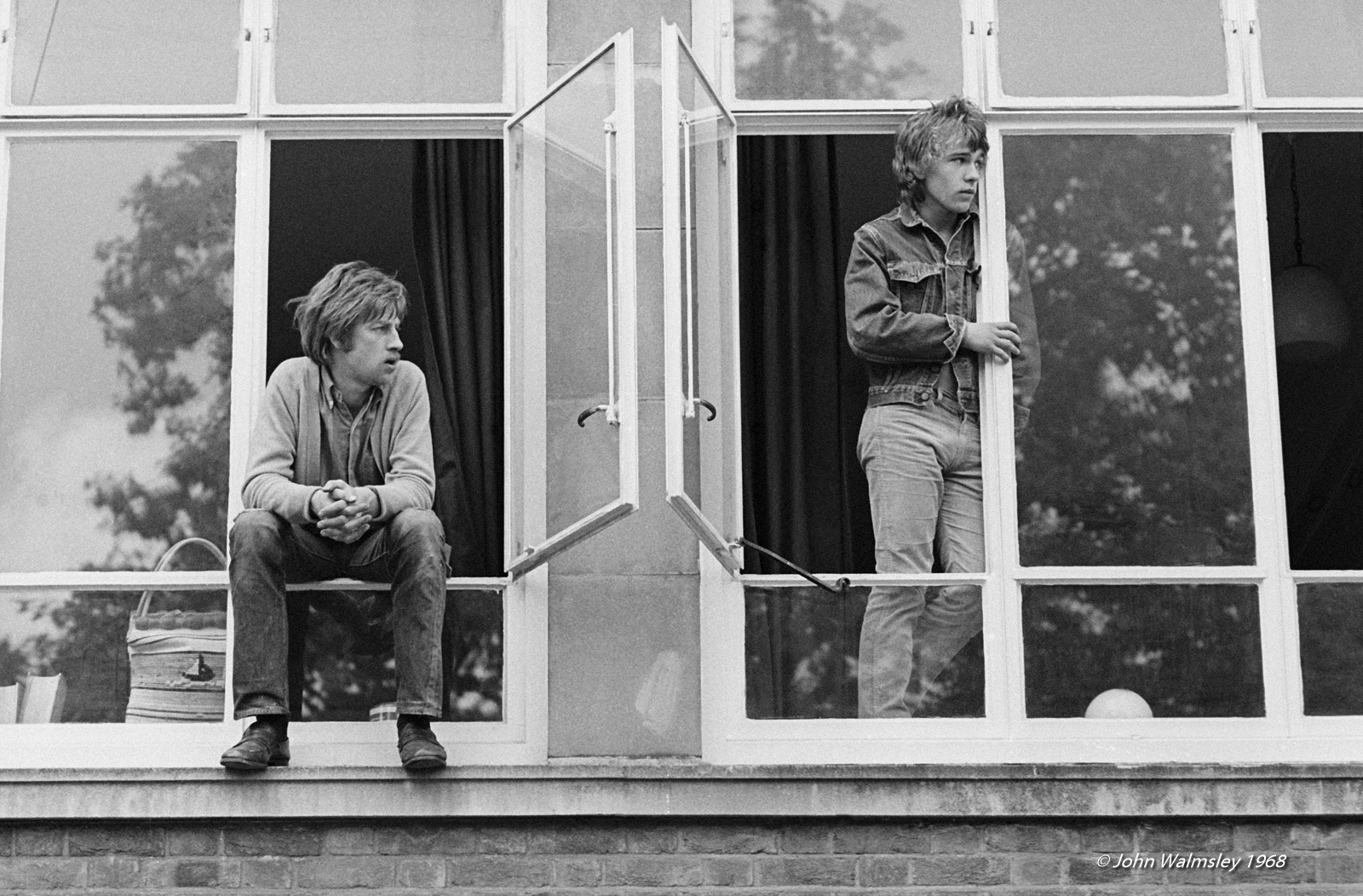

With a cynical elite in control, inevitably this current revolt is often compared to the protests of another era – we see the cars burning and think of May 1968. Though these photos feel like they could have been taken 50 years ago, the two movements are very different.

When I was in high school, I demonstrated. I found my comrades wrestling Place de la République. We advanced valiantly towards La Bastille, then Nation. It would never have occurred to us to march on the Champs-Élysées – the Champs was for tourists and pickpockets; it is one of the symbols of the “beautiful districts” of Paris. Now, it stands as the place of protest of the Yellow Vests, representing the radically different nature of this revolt.

“Presently, we are in a depression, a shared desperation of mass unemployment. We hope to “change life” – in the manner of Rimbaud – by indulging in revolt.”

In May 1968, France was in a period of growth. There was hope for the future. We wanted to "transform the world" in the manner of Marx – to make the revolution for ourselves. History was moving forward in the positive. Presently, we are in a depression, a shared desperation of mass unemployment. We hope to "change life" – in the manner of Rimbaud – by indulging in revolt.

The casseurs [breakers] are at odds with the protests of ‘68, however. These casseurs are on the sidelines of the demonstrators yet center-stage for the global media. They engage in well-organized chaos. They protest in order to break, destroy, and release their rage; to terrorize what they see as the materialism of central Paris. But these casseurs have little connection to the protester’s demands.

“Today, a self-proclaimed security squad has appeared on the scene, made up of extreme far-right figures who, like the casseurs, have nothing to do with the movement itself”

In 1968, to assure that the protests didn’t degenerate, ‘security’ was run by CGT members – the syndicalists who launched the movement themselves. Today, a self-proclaimed security squad has appeared on the scene, made up of extreme far-right figures who, like the casseurs, have nothing to do with the movement itself. They claim they do not attend the protests to recuperate the movement, but for provocation: “parce que les révoltes sont stériles” (because revolts are unproductive), said Yvan Benedetti, an infamous French nationalist. They are staging a political ‘subversion’ of the movement, using the visibility of the protests to disseminate hateful conspiracy theories.

Nevertheless, the Yellow Vest invasions continue. They leave the provinces together, hand-in-hand, to come and protest at the most famous Parisian artery in the world. They leave the Arc de Triomphe, and descend, imperturbable, as far as Concorde, as far as the Louvre, as far as La Bastille. And all those private, royal monuments become the real witnesses to this generation’s revolt.

Mathieu Richer is a French photographer based in Paris. Fueled by his passion for travel, he has photographed a diversity of communities all over the world.

Léa Boehringer is a French writer based in Paris. She writes for Canal+ and is currently working on a novel about the socioeconomic divide between Paris and the provinces.

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.